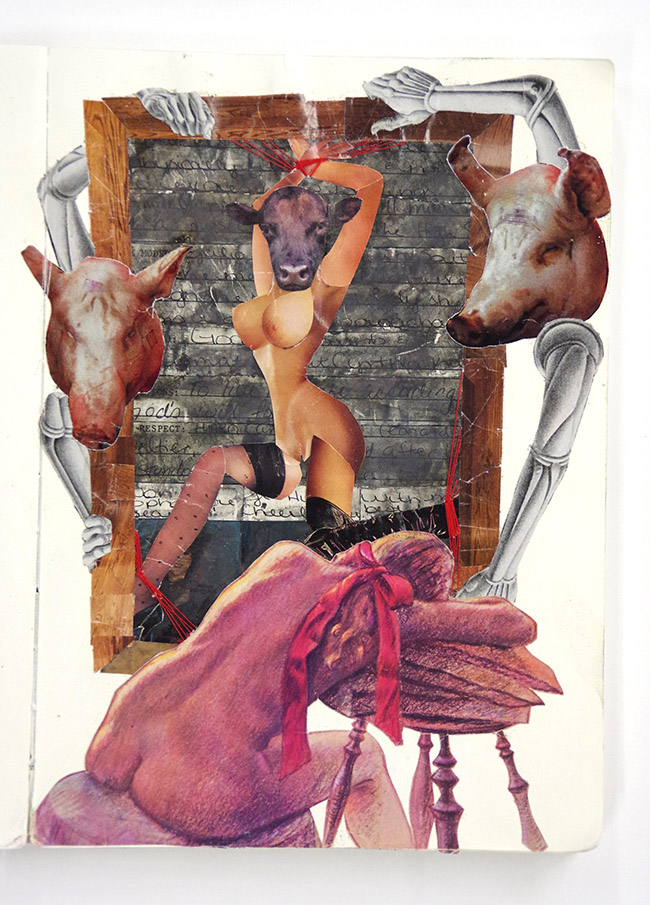

To Be a Girl, To Be a Woman

Emma Mae is a visual artist based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The Uncanny Legacy of Aunty Badass Sage

Jessica Wierzbinski

At leastourmom finished raising us before she abandoned us. Many of my cousins were not so lucky. It’s something of a pattern with Hague women, evidently, though God only knows why.Theirmama didn’t turn holy roller on them in her final years. I mean, she was as pious a Catholic as you’d ever want to know, Grandma Ellen. So why so many of her progeny took it overboard remains a mystery as dark as the catacombs of ancient Rome itself. Grandma Ellen had 15 children, 13 of whom survived into adulthood and propagated almost as prolifically as she and Grandpa Delbert had. The oldest daughter of the bunch, Sage, was something of a trailblazer as it turned out, laying a boldly confident path through life that many of her sisters would come to emulate, much to the chagrin of their derelict husbands and children. Aunt Sage was already ancient and still beautiful by the time I got to know her. (I was grandchild number 73 out of 79, mind you, so I didn’t join the Hague family melodrama until well into its 20th century conflict, or climax, or whatever the hell it was, that tangled collision of so many burning hearts with so many broken ones.) That summer, my sister and I were shipped off to stay with Aunt Sage for a couple of weeks for reasons that are still unknown to me but likely due to some manner of maelstrom my immediate branch of the Hague family was struggling through. No doubt crippling poverty compounded by the interpersonal conflicts that are inevitable when two teens, my parents, find themselves suddenly raising an endless succession of babies. No one tells a nine-year-old kid these things; you just ship her off somewhere safe for a bit and hope everyone else weathers the storm okay and you’ll pick her up on the other side. As far as I could tell, Aunt Sage was pure badass, tinged here and there with a spot of uber-piety that both mystified me and scared me a little. But that summer, I focused on the badassness. She had built her own log cabin home on a beautiful, verdant spread of rolling hills somewhere along the placid waters of the mighty Missouri River. She wore her silver hair in a loose, efficient bun on the top of her head, and that was how I’d seen her all my life. But staying with her that summer, I got to see another, softer side of Aunty Badass. In the evenings, she let her silver strands hang down around her elegant, sturdy neck.Wow,I thought.If I’m ever an old woman, there’s no way in hell I’ll have short hair like most of them do.I couldn’t wait to have stringy, silver whisps alongside sun-leathered, high-set cheeks. During the days of that summer, I helped Aunt Sage lay bricks for a walkway she was building to the back acres of her land. I was an inherently lazy child, much more prone to academics than manual labor, but somehow this woman got free and easy labor out of me. I’m not sure if it was pure admiration on my part, or hope in her confident, homespun promises. “Every brick you lay gets a soul out of the agony of purgatory and into the glory and bliss of heaven,” she told me, and I believed her as a matter of course. I’d had only a cursory education in Catholic teaching by that point—nothing like the decade plus of Catholic schooling that lay ahead of me, but more on that later. At age nine, I was still somewhat insulated from the particular brand of Midwestern Catholicism that so enveloped the rest of my prodigious family. This striking, strong woman was my first teacher in that school of thought, and I trusted her implicitly. “How do you know that?” I asked hesitantly, not wanting to show my ignorance but hungry to learn how the economy of salvation worked. “Know what?” she asked, her nimble mind no doubt already on to the next topic of rumination. “That bit about the bricks and the souls in purgatory,” I said. “Oh that,” she chuckled. “Well, it’s not like it’s written in the Bible or doctrine or anything. But I told God that was the deal. I told him I’d build a house of prayer for him and his flock out there.” She nodded toward the sprawling back acres of her land. “Told him if I’m going to lay all these bricks and make a space for that, the least he could do was let a few souls off the hook early.” She chuckled again and we both went on laying down bricks and covering them with crusher fines from the pails we carried along with us.Dang,I thought.She talks to God. And evidently, she tells him how it’s going to work. Years later, Sage would build the promised retreat center on those back acres and donate the whole complex to her local church. It’s still there; look it up: The Mir House of Prayer, just outside of St. Joe’s, Missouri. Her legacy. I’d been vaguely aware in those days that she had kids, cousins I’d seen a few times across the years but never connected with because they were a state away and old enough to be my parents. That summer I didn’t know where they were and she didn’t talk about them. It would be years before I met one of them, a daughter with strikingly angular cheekbones and a beautiful smile, every bit her mother’s daughter. Except perhaps in the bits that mattered. “Yep, she built that cabin,” cousin Annie confirmed my childhood memory when we met over beers some 30 years after my Missouri summer. But Annie’s voice did not mirror my enthusiasm. “And yeah, she went on to build the Mir House too. But there are things about her you can’t understand, Jess.” I pressed a bit, but Annie was tight-lipped. “Dad wasn’t her fondest love,” she finally offered. Almost instantly she noted my raised eyebrows and nearly choked on her swig of beer. “Jesus,” she clarified, “I don’t meanthat.She was frigid as witch’s tit.” We shared a laugh then, and another beer. When Annie was sufficiently lubricated, she came around to telling me that maybe it was her old man’s demanding nature that had turned Sage frigid, or maybe the causality went the other way around. How could a kid tell? “All I know is that sometime after bringing all us kids into the world, me and my four siblings, she reneged on the whole motherhood side of the bargain and decided to become a nun instead. I mean, notipso facto,of course, but a nun for all practical purposes. She left us to our own devices and ran off and married the church instead.” Annie was right; I hadn’t understood any of that. But I would come to understand some watered-down version of it in the years that followed. My own mother had dedicated her life to her children. Not that she was ever the doting sort. Far from it. She was—I won’t say cold, but tepid at best. Preeminently dutiful, and perfunctorily efficient in the fulfillment of every self-laid duty. She saw to all our physical needs unflaggingly. I recall vividly one summer afternoon my awkward, 14-year-old lankiness hemming and hawing around behind her as she hunched over her sewing machine mending something or other from our wardrobe, no doubt extending its working life and enabling it to be handed down to the next one in line. I needed to tell her I’d started my period. It had come two years prior but I’d never told her, and now it was starting to feel like a lie I was carrying around. Shouldn’t she have asked at some point? My friend Teresa said when she started hers, her mom took her on a special, weekend-long shopping trip and baked her a “Welcome to Womanhood” cake. That sounded like hell. Maybe that’s why I hadn’t told mom yet. But no, I reasoned, there was zero risk ofmymom fussing and gushing over something as mundane as a little blood in the underwear of her fifth child. So why the hell am I still fidgeting around behind her instead of just telling her so I can get on with it already? “Oh hey,” I blurted out finally. “I started my period, okay?” “Ah,” she said, glancing up from the seam she was busy with. “Is that what you’ve been trying to say for the past half an hour?” She chuckled and shot me a quick look over her shoulder before returning to her stitching. “You know what to do, right? Your sisters should have plenty of pads and whatever in that basket over the toilet.” And whatevermeant tampons, I deduced. My older sisters had told me gigglingly that it had taken them years to convince Mom to buy them tampons. Tampons hadn’t existed when Mom was a girl and she mistrusted anything that went inside the vagina, fearful that it might bring sinful pleasure. “Mom,” Angel had chortled with her voice full of eyeroll, “It’s the size of my pinky, comeon.” “Yeah,” I replied, relieved that the conversation was over. “I know what to do.” Some decade plus later when her six children had all flown the coop, she left my dad and traded our shared surname for her childhood one, Hague, a fact we siblings tried not to read too much into until we realized we were deluding ourselves if we refused to see her regression. She devoted herself wholeheartedly, nun-like, to the sacred heart of Jesus. She read holy books for multiple hours a day, pausing only to make herself a meal, go to Mass, and play bridge with her sisters on Thursday afternoons. She carried around a holy card of St. Michael the Archangel pinning some horned, dragonesque beast to the ground with his foot and wielding his huge sword menacingly above it. On the back of it was printed the Prayer to Saint Michael, in which the faithfully indignant implore the justice-bearing angel to “thrust into hell Satan and all the evil spirits who prowl the world seeking the ruin of souls.” I’d memorized that one, along with a slew of similar trepidation-inspiring prayers, in second grade, as preparation for my first communion. Age seven. When Mom was 74, my siblings and I decided to spend some quality time with her. Since—but statedly not because of—the divorce, mom had seemed depressed and withdrawn, and who wouldn’t be, left alone with those awful, nightmarish prayers and that world-damning literature? So we rented a big house near Olpe, Kansas, the tiny town she’d grown up in, and we intended to spend the weekend touring around the area, listening to her rehash fond, old memories of the places that had cradled her tender years. (Even she must have had tender years, right?) Instead, we ended up spending almost the entire weekend at the Olpe parish auction with a bunch of Mom’s brothers and sisters. The town of Olpe was poised to raze their hundred-year-old school building and replace it with a metal monstrosity of a parish center, so they’d planned a grand, weekend-long auction to sell off anything salvageable inside the ancient building before its demise. Mom had planned to go to the auction long before we’d plotted our togetherness weekend idea. In true Mom fashion, she had succeeded in not letting us alter her plans in the least. Well, except for the fact of our being present in them, which she made amply clear was an irritating inconvenience throughout the weekend, and an outright embarrassment at certain points. Like when my siblings and I found utter hilarity in my securing from the slick-tongued auctioneer the blonde-haired, blue-eyed baby Jesus doll that Olpe parishioners had used for decades in their Christmas pageants and Nativity scenes. I tucked it in my backpack, its porcelain, fat-cheeked face emerging from the top of my pack. We knew we were flirting with the delicate boundaries of sacrilege, especially later that evening, back at the Airbnb, when my brother hung the creepy Christ child from the ceiling fan chain. That was when we’d certainly taken it too far. But Mom’s preference for her siblings’ company to ours had already amply conveyed that our weekend plot had been a failure, so we had nothing left to lose. Figured we might as well have some fun with each other at least. Someday I’ll tell you more about some of my other aunts, the infamous coven of nine strikingly beautiful and staunchly self-determined Hague women. But this—the tale of the eldest, that trailblazer Sage; and my mom, the baby of the tribe—this is enough for now. I have to process all this in manageable morsels, you understand. These are my foremothers, my origins and my presumable trajectory, and I haven’t even finished growing up yet.