It's often been said that every story has already been told and that each new story is nothing more than an iteration, a reiteration, a reinterpretation, or simply a retelling. Saramago's stories are evidence that this assertion is not true. This is primarily because Saramago's writings explore permutations. Mathematically, permutations are a way of arranging a given set of variables. Saramago imagines the variables one might encounter in a particular situation and explores the infinite in their possibilities by masterfully offering his readers multiple narrative avenues. This complex approach speaks to his capacity to remain familiar and refreshingly "new" in his stories. The tales challenge the common notion of order and embrace the chaos that ensues in its pursuit but are rewarding as they continue to unfold in your mind long after the text has been read.

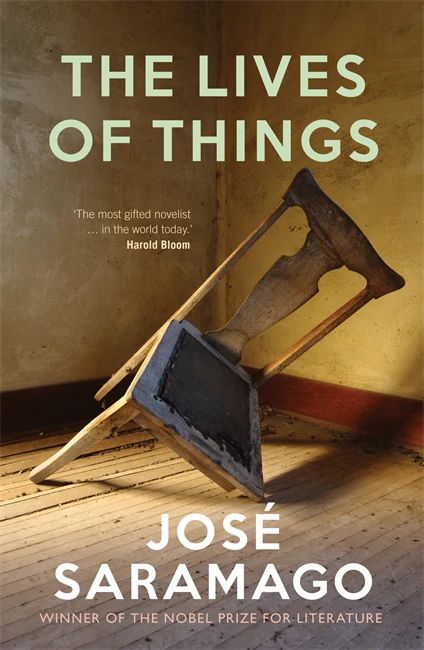

In "The Chair," the opening story from his collection, the reader is invited to explore a piece of furniture, a chair. Not just any chair, but the deck chair that supposedly collapsed under Portugal's longtime dictator António Salazar, which (allegedly) resulted in a cerebral hemorrhage and the man's eventual demise. Saramago, instead of examining the man, chooses to focus his readers' attention on the chair. For instance, we meet the termites that have burrowed into the wooden legs and weakened the structural integrity of the chair. These creatures have a rich life as Saramago anthropomorphizes them as western gunslingers fighting over a woman. It's this hidden world—and the events that occur there—that influence the known world. This theme recurs throughout many of Saramago's stories.

Rarely do Saramago's characters have names. His perspective encompasses the human condition, and although he does address the individual, it's often in terms of archetypes: the king, the reporter, the groundskeeper. From this vantage point, his stories take on both the political and the situational. In "Embargo," Saramago depicts one man's unwilling escapade in a car that travels from one fueling station to another under its own volition during the Arab oil embargo of the 1970s. His embarrassment over purchasing a mere liter of fuel after waiting hours in a fuel line is meant to evoke a larger message about consumerism and the hunger--as awkward as it is--that it demands.

"Reflux," another story in the collection, is an allegorical tale that explores the absurdity of a society that believes in the infallibility of its "royal personage," which, of course, could easily be read as any political leader, politician, or bureaucrat who rules with absolute authority. In a distinctly Kafkaesque style, Saramago delineates the herculean task of the exhumation of all the deceased of the entire country and the relocation of these corpses into a single expansive and walled graveyard. The undertaking (pun intended), meant to remove the specter of death from the monarch's purview of perception, inevitably results in unintended consequences that reveal the ruler's limitations and also comments on the larger aspect of humanity's futile attempts to regulate things beyond their control.Saramago's precise and eloquent prose can be halting at times as be sets out to clearly define and describe situations and thoughts while simultaneously acknowledging and qualifying alternative narrative possibilities, but it is his wit and verve that give his meanderings a smart playfulness. To enjoy this collection, one must not only be accepting of Saramago's circuitous storytelling but one must embrace the notion that the journey is the destination, and that order is not the aim.

Dr. JOHN SCHULZE

Midwestern State University

Originally published inPrairie Schooner,Volume 87 Number 2, June 2013.